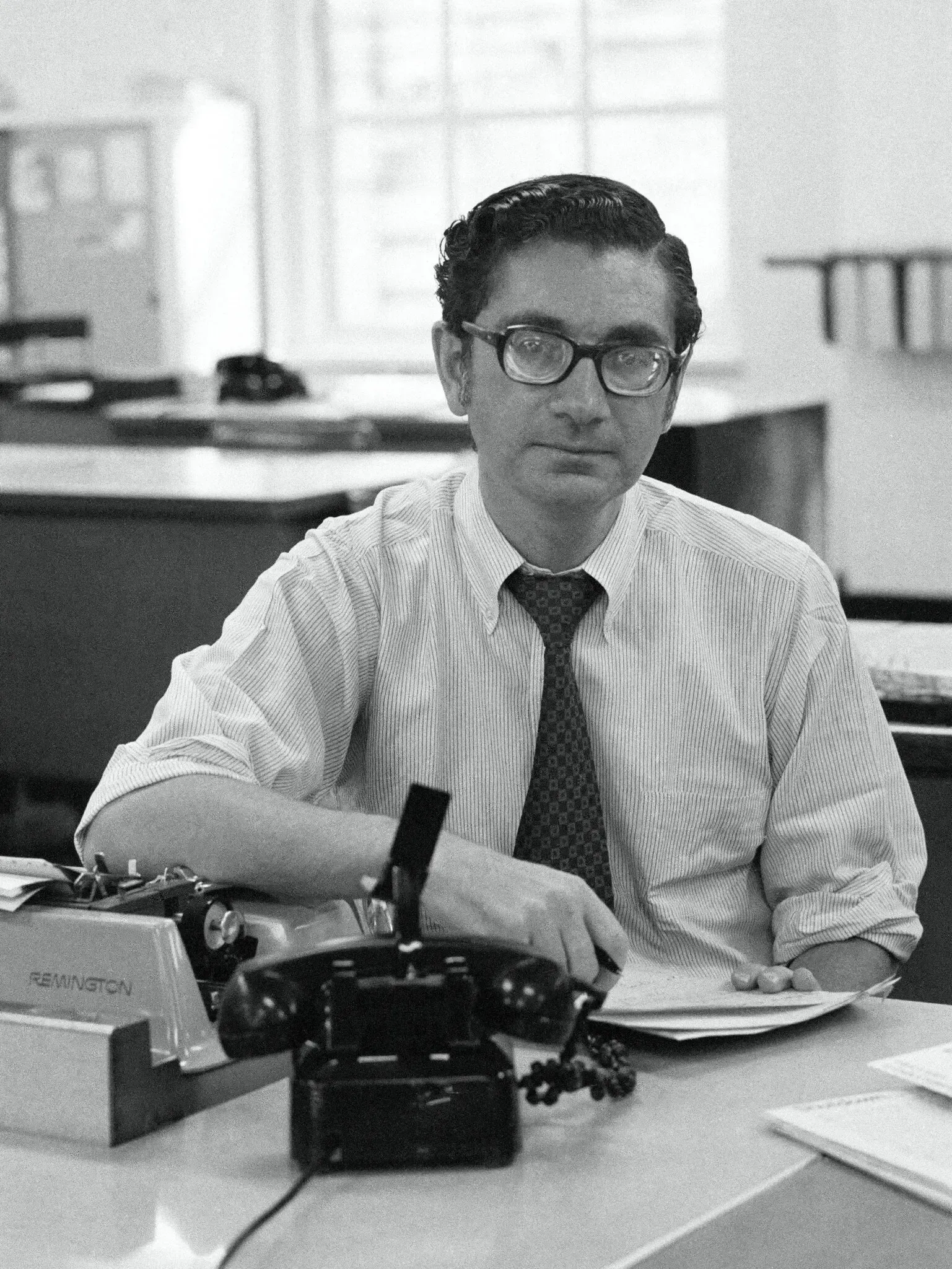

Mimi Sheraton

Restaurant Critic Extraordinaire

At The New York Times in the late 1970s, a newly divorced man had no better friend than Mimi Sheraton. Needing tasters as she headed off to a restaurant destined for her scrutiny, she on occasion rounded up colleagues whose marriages had broken up. In those days they were almost always men, the sort who tended to be short on cash and even shorter on decent meals. Whatever restaurateurs may have thought of Mimi – and more than a few of them felt irredeemably bruised by her reviews – she had her colleagues’ hearts.

Mimi, who died on April 6 at age 94, was The Times’s restaurant and food critic from 1976 to 1983, but the newspaper was only one of her way stations across six decades of thinking about food, caring about food and, of course, writing about food, typically in no-nonsense prose and a brook-no-disagreement voice.

Her career took her to a slew of magazines, among them New York, Vanity Fair, Time and Condé Nast Traveler. She wrote a shelf’s worth of cookbooks, restaurant guides and a resource for trenchermen, “1,000 Foods to Eat Before You Die.” As Bob McFadden noted in his stately obit for The Times, Mimi “calculated in 2013 that she had eaten 21,170 restaurant meals professionally in 49 countries.” One of the 49 was Israel, which she visited in the early 1990s with her husband, Richard Falcone. I was then The Times’s Jerusalem bureau chief and spent some time with them. After a few meals, Mimi decided that Israel was in no danger of landing on any discerning diner’s list of countries one absolutely must visit.

As the first woman to review restaurants for The Times, she resorted to various wigs and glasses, though how successful she was at disguising herself may be debatable. Suzanne Charlé, a Silurians board member who first met Mimi in 1973, recalled a time when Mimi, while ordering a meal, “turned her head quickly, and the wig tilted on her head.”

A memorial service was held on April 17 at Frank E. Campbell. In what may very well have been a first for the funeral home, pews were dotted with laminated copies of a recipe for chicken soup. It was, of course, Mimi’s recipe. No, the first step was not to steal a chicken. But it did begin with an admonition that “root vegetables are essential to this soup.”

The final speaker at the service was her son, Marc Falcone, who mentioned his mother’s disguises. “My dad, however, dined with her always and never wore a disguise, inspiring a short-lived rumor that Mimi Sheraton was, in fact, a man,” Marc said. “Her instinct about wearing the disguises was never so clearly confirmed as it was when an expensive restaurant seated us at a table so uncomfortably close to the kitchen door that every time the door swung open it revealed a photo of her with a large caption that said THIS IS MIMI SHERATON.”

Mimi’s diligence was legendary. How many people would gather 104 pastrami and corned beef samples in a single day to evaluate their viability in sandwiches? Or taste all 1,196 items sold in Bloomingdale’s food department? Or brew 97 pots of tea to test their worthiness?

She knew what she liked and didn’t like, whether the cuisine was haute or basse. Take the bagel. Who better to discuss its merits than Mimi, author of a book on the bialy, first cousin to the bagel. I once rang her up for a column on the state of New York bagels, and she wasted no time telling me, “In general, I think it’s deplorable.” Ideally, a bagel should be about 3.5 inches in diameter, she explained, but most tend to be a good deal larger. Their thickness “makes them like rubber tires,” she said.

As suggested by the lunches with no-longer-married colleagues, hers was a generous spirit. Linda Amster, the Times’s former chief researcher and editor of “The New York Times Jewish Cookbook,” said that Mimi wrote not just the introduction but also the prefaces to sections about each course of a meal. “And,” Linda said, “she also joined me at a Barnes & Noble appearance to publicize it.”

That generosity was evident in Mimi’s return to Midwood High School in Brooklyn, where, as Miriam Solomon, she had graduated in 1943. In 2004 she went back to help teach a writing course. She stretched the students’ vocabulary via meals. “Everybody eats and has opinions about food,” she said. No exception, her students found the school cafeteria’s French fries to be soggy and the hamburgers rubbery. And don’t start them on vegetables. “You can lead a horse to water,” Mimi said with a sigh, “but you can’t make it eat the broccoli.” – By Clyde Haberman

Obituaries

Milton Esterow, Who Brought an Investigative Edge to Stories About Nazi-Looted Art, Dies at 97

The ‘Heart and Soul of the New York Post,’ Myron Rushetzky, 73, Loses Battle with Cancer

Top Editor, True-Blue Silurian, July 5, 1933-June 1, 2025

The Pulitzer Prize-winning correspondent and former Executive Editor was the public ideal of a New York Times man: polished, erudite and well spoken.

Author, Actor, Politician, All with Irish Flair, 92

Village Voice Co-Founder, Publisher, Soldier, Psychologist, 100

Iconoclastic Reviewer of Our Most Popular Medium

Stephen M. Silverman, age 71, reporter and historian of popular culture, died on July 6, 2023. The New York Post’s chief entertainment correspondent for years and a founding editor of people.com, he has contributed to publications across the United States and abroad, and taught journalism at Columbia University. Among his more than a dozen books are “David Lean,” “The Catskills: Its History and How It Changed America” and “The Amusement Park: 900 Years of Thrills and Spills, and the Dreamers and Schemers Who Built Them.” There will be a celebration of his life this fall after the publication of his last work, “Sondheim: His Life, His Shows, His Legacy.” He is survived by a niece, Sarah Silverman, and many devoted friends. Memorial gifts in Stephen’s name can be sent to PEN America (pen.org). Published by New York Times on Jul. 9, 2023.

Grace O’Connor, a Silurian since 1997, an award-winning reporter and editor for the Albany Times Union for 22 years, and one of the first women installed in the Hall of Honor of the Women’s Press Club of New York State, died October 29, 2022 at Branford Hills Health Care Center in Connecticut. Paul Grondahl, a former colleague at the Albany Times Union, was moved to write an appreciation, excerpted here in part: “She was old enough to be my mother and she kept a Holy Bible atop her beige metal desk, next to an IBM Selectric typewriter and rotary telephone. Grace O’Connor did not drink or curse, which, along with the Bible, made her an outlier in the rough-and-tumble bygone era of newspapering. She was on a first-name basis with half of Albany. There was only one Grace. “She was beloved by her readers and coworkers alike,” said Barb Zanella, who began as an editorial clerk at the Times Union in 1973 and worked for Grace, whom she considered a mentor and later a dear friend. A former Baptist Sunday schoolteacher, Grace brought out the better angels of the hard-drinking, cynical 20-something reporters who worked alongside her…. “There was nothing phony about Grace. She was aptly named,” said Fred LeBrun, who arrived at the Knickerbocker News in 1967, moved to the Times Union in 1970 and worked as reporter, editor, restaurant critic and columnist and who still contributes a monthly column. Grace became a kind of den mother to an unruly crew of scribes who helped pound out the first draft of history. She regularly quoted Scripture in her feature stories, which graced the Times Union from 1969 to 1991. She got her start writing for the paper’s five weekly neighborhood supplements, known as the Suns, and later served as the Suns’ editor before becoming a general assignment reporter for the main broadsheet….” For more: https://www.timesunion.com/news/article/Grondahl-Remembering-a-newsroom-full-of-Grace-17567547.php Born in Long Branch, NJ on September 13, 1927, O’Connor graduated from Manasquan High School in 1945, and attended Monmouth Junior College in Long Branch and Rutgers South Jersey in Camden, NJ. While a teacher and director of Bethesda Lutheran Nursery School in New Haven, she was published regularly in magazines, including “Ingenue,” “Teen,” and religious publications. As a community leader, she was President of the East Camden (NJ) Junior Women’s Club and a member of the state board of the New Jersey Federation of Jr. Women’s Clubs in the 1950’s, a member of the Branford, Connecticut Women’s Club in the 1960’s, and served on the board of the Community Dining Room in Branford. O’Connor is survived by her daughter Patricia and her son-in-law Carmen Cavallaro, grandsons and beloved great grandchildren who called her “Grandma Grace.” A celebration of her life and memorial service will be held at the First Baptist Church, 975 Main Street, Branford Connecticut on November 12 at 11:00.

A swell fellow, a proud Silurian, that all-round nice guy, Jim Lynn , left us on Aug. 10 due to complications from Covid. He was 88 and a retired editorial page writer at Newsday, where he had worked for 30 years. Jim, a Princeton University graduate, went to Newsday in 1972 after stints at The Long Island Star-Journal, Newsweek, New York Herald Tribune, WABC-TV and WMCA radio. He was the Trib’s Albany bureau chief in 1966, on vacation in Europe when he got word that the paper had shut down. His former colleagues at Newsday had nothing but awed references to Jim’s intelligence and wit. James Klurfeld, editorial page editor for Newsday from 1987 to 2007, remembered his friend and colleague as someone who represented old-fashioned virtues. “He was a terrific editor, a very careful fine, fine editor who always improved your writing,” Klurfeld said. “He improved my writing. I won an award for best editorials one year and I owe it all to Jim who I often showed my material to before I published it.” Carol Richards, editorial page deputy editor from 1987 to 2006, said that during those years the editorial board was strong with smart, passionate people whose political leanings covered a wide range of beliefs. Lynn was the person to count on to be informed on liberal politics. “When we were having a debate about some issue, almost always political or governmental, Jim had opinions that people would listen to,” she said. “He wasn’t a knee jerk liberal; he was a well-informed liberal.” “He always said he felt so lucky to have had the opportunities that he had,” his daughter, Nina Lynn said. “He also felt a great responsibility to use what he had been given, well and honorably.” James Dougal Lynn was born in Houlton, Maine, and graduated from high school in Mount Lebanon, Pa., where a teacher recommended that he apply to Princeton. His experience there set him on a life-changing course, his daughter Nora Curry said, which included his first introduction to bagels. “His world opened up in so many ways. He made lifelong friends, he got to be with other people who loved reading and writing and thinking the way that he did, he’d not had that before.” Dora Potter, Newsday alum, fellow Silurian and his devoted partner of 30 years, said Jim was “thoughtful of everyone.” Besides obvious acts of community service such as after he retired volunteering as a dispatcher for the local fire department, he would do unexpected, ordinary things that would never occur to others. He packed up his extensive collection of Playbills and took the train in from Long Island to give them to an Aids center for actors. He lugged interesting beer cans he’d picked up all over Europe to the delight of a friend back home who had a collection. “He never stopped thinking of others,” Potter said. “He was a steward for us all, he took care of us.” His daughters agreed, saying their father gave them a set of values to live a life with empathy and public service. He made one final act of public service: he donated his body to science. “To my dad it was sensible,” Nora Curry said. “It’s like ‘someone can use this and learn from it.’” A memorial was scheduled for Nov. 6 at the Nassau County Museum of Arts in Roslyn, where Jim was a docent. Potter said it would be both in person and on Zoom. She said she particularly wanted that option so people can choose to be safe, since both she and Jim had suffered from Covid.—By Theasa Tuohy

Frank Leonardo’s gifts of gab and camaraderie were on full display about once a month when a group of us pre-Murdoch New York Postniks congregated for breakfast at an Upper West Side diner to schmooze and reminisce. It was like Old Jews Telling Jokes except two of us were Italian. We told newspaper war stories. We vied for equal time, like GOP wannabe presidential candidates at a Fox News debate. Frank was often a step ahead. He was the only shutterbug among a bunch of scribes but that didn’t matter. He was well-read, a polymath and just as attuned to the literal side of a news story as any writer. He sometimes pissed off his reporting partner at interviews when he would lay down his camera and pose his own questions for the subject. Most of us, however, tolerated the habit. “They were good questions,” said Clyde Haberman, a charter member of the breakfast club. While Frank may at times have thought a word was worth a thousand pictures, that didn’t mean he wasn’t a crack photographer: He won two awards from the New York Press Photographers Assn., first prize in breaking news for a photo of a fireman carrying a rescued child down a ladder; and second prize for the photo of a diving polar bear, which is still a source of mirth for the Leonardo family. “I know that category was called ‘animal,’” said Frank’s wife Barbara Garson, “because I remember laughing at the plaque, which read ‘Frank Leonardo Second Class Animal.’” He did not seek plaudits. “He never entered photos into any contest including the Press Photographers,” Garson said. “In that case, I believe a former girlfriend did it for him.” Frank was born in Brooklyn in 1937. His father Thomas, also a photographer, was killed in action in World War II when Frank was eight years old. He and his mother Helen then moved to the Parkchester section of the Bronx. This early history of loss and upheaval became the blueprint for a bumpy road. Garson said young Frank dropped out, or was kicked out, of five New York City high schools before receiving a diploma from Theodore Roosevelt Night School in the Bronx. He then somehow won a scholarship to NYU, where he earned a degree in geology. Along the way, Frank met and married his first wife, Dorothea Snyder, mother of his two children, Cecilia and Thomas, who survive him. His early interest in geology waned and — Voila! — he landed a job as a news photographer for the French news service Agence France-Presse. His 40-year career was launched by catching the magic in a moment of history: Frank was the pool photographer on the roof of Montreal City Hall on July 24, 1967 when General Charles de Gaulle electrified thousands of wildly cheering Quebecois — and stirred an international uproar — by declaring, “Vive le Québec libre” (“Long Live Free Quebec”). Though Frank, says his wife, was not dazzled by celebrity, he was deeply impressed by de Gaulle’s magnetism and stature. No record exists of whether he felt the same way about The Fab Four when, on February 7, 1964, when their Pan Am Boeing 707 landed in New York. A photo of their raucous arrival at JFK records his presence among the scrum of photographers gathered behind a metal barrier. Frank also appeared in the famous documentary movie “Harlan County, USA” where he is seen filming a picket line of striking coal miners in rural Kentucky. He also witnessed the real-life event that inspired the 1975 Sidney Lumet movie “Dog Day Afternoon” when three shotgun-toting men besieged a Chase Manhattan bank in Brooklyn in an abortive attempt to trade hostages for money. Frank had little interest in the glamorous or thrilling sides of his profession. In his leisure time he enjoyed puttering with his 20-foot-long Cadillac Fleetwood Brougham (“He could fix anything,” said a family member) and he was an avid kite flyer. He owned dozens of kites that he liked to fly in the Sheep Meadow using a deep sea fishing rig to “have his own set of wings to become a bird in flight,” to paraphrase Mary Poppins. Frank Leonardo’s final job before retirement was as photo editor at CMP, a computer trade magazine. In this position he once asked a major photo agency to send him photos of subway turnstiles. One of the photos bore his own byline. ‘He called them wondering where they got it and they volunteered some pay,” said Barbara Garson. “That was the only time he ever followed up any newspaper photo of his.” That was Frank. He died of cancer on July 26 at age 86. The shutter fell and the light is extinguished. —Anthony Mancini