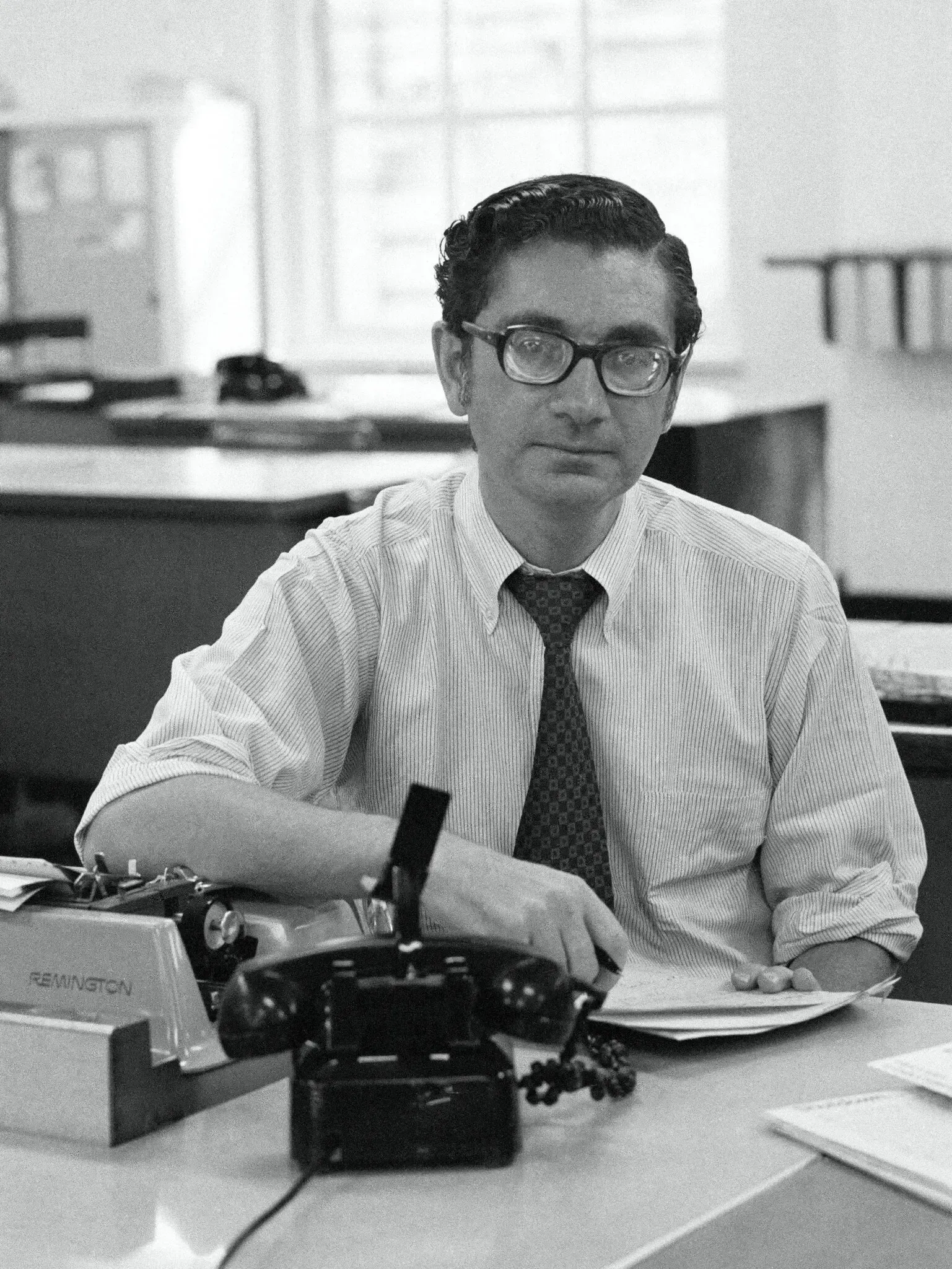

Malachy McCourt

Author, Actor, Politician, All with Irish Flair, 92

Malachy Gerald McCourt, who was at various points – and in no special order – an actor, a saloonkeeper, an author, a dishwasher, a dock worker, a radio host, a smuggler and a Bible salesman – chose in 2006 to add political candidate to his résumé. He ran for New York governor that year.

Actually, showing his Irish roots, he said that he was “standing for office.”

Why American pols run for office and those on the other side of the Atlantic stand is not clear. Could it be that our politicians need a head start? In any event, Malachy ended up quite admirably in third place as the Green Party nominee. If only he had managed to pick up another 3,044,544 votes, he would have edged out the fellow who did win, Eliot Spitzer.

The sad part of it, he decided when I interviewed him before the election, is that American politics can be hopelessly grim. Their essence is “the inculcation of fear – fear and the evil of your opponents, what awful, dreadful, less-than-human beings they are,” he said. “Until elected. Then they say ‘We have to get behind them.’ ” Not much has changed on that score except perhaps the get-behind-them part.

Malachy died in March at age 92, weighed down with more ailments than need be listed here. Inevitably, he was at times paired and compared with his older brother, Frank McCourt, who died in 2009 and whose runaway best seller, “Angela’s Ashes,” affirmed that being wretchedly poor is not an ideal way to grow up. “I was blamed for not being my brother,” Malachy lamented. But he bore that burden well. Fact is, he had a best seller of his own in 1998, “A Monk Swimming,” the title evoking how as a boy he had misheard the Catholic reference to Mary as “blessed art thou amongst women.”

In his splendid New York Times obituary, Sam Roberts quoted Malachy’s advice to anyone writing a memoir: “Never show anything to your relatives.” Back in 1977, the brothers McCourt were trying out a play they had written, “A Couple of Blaguards,” which they declared to be “a lighthearted look at Ireland.” Unfortunately for them, their mother, Angela, was in the audience during one performance, and she stood up and said, “It wasn’t like that! It’s all a pack of lies.”

As the years passed, Malachy decided that “every day above ground is a good one” and that a desirable goal for us all is to “stay on right side of the grass.” When I interviewed him during his race for governor, he dutifully ran through his campaign themes – serious matters for sure, like his opposition to capital punishment, to tuition charges at public colleges and to the then-raging war in Iraq. But he had other issues as well. Perhaps reflecting an instinctive Irish distrust of anything British, he wanted New York to drop its claim to be the Empire State. He favored a tax on tobacco so high that a single cigarette would cost the same as a gallon of gas.

Oh, and he was prepared to triple the tax on chewing gum. Gum chewers look stupid, he decided. And then all too many of them simply spit it out. “It does terrible things to the sidewalk and the subway,” he said.

But while his gubernatorial race was in no way intended as a joke, he cautioned against taking oneself too seriously.

Terminal solemnity is the curse of all too many in the political class, he said (and, he might well have added, of more than a few journalists). To reinforce the point, the well-read Mr. McCourt offered a quotation from the English writer G.K. Chesterton: “Angels can fly because they take themselves lightly.