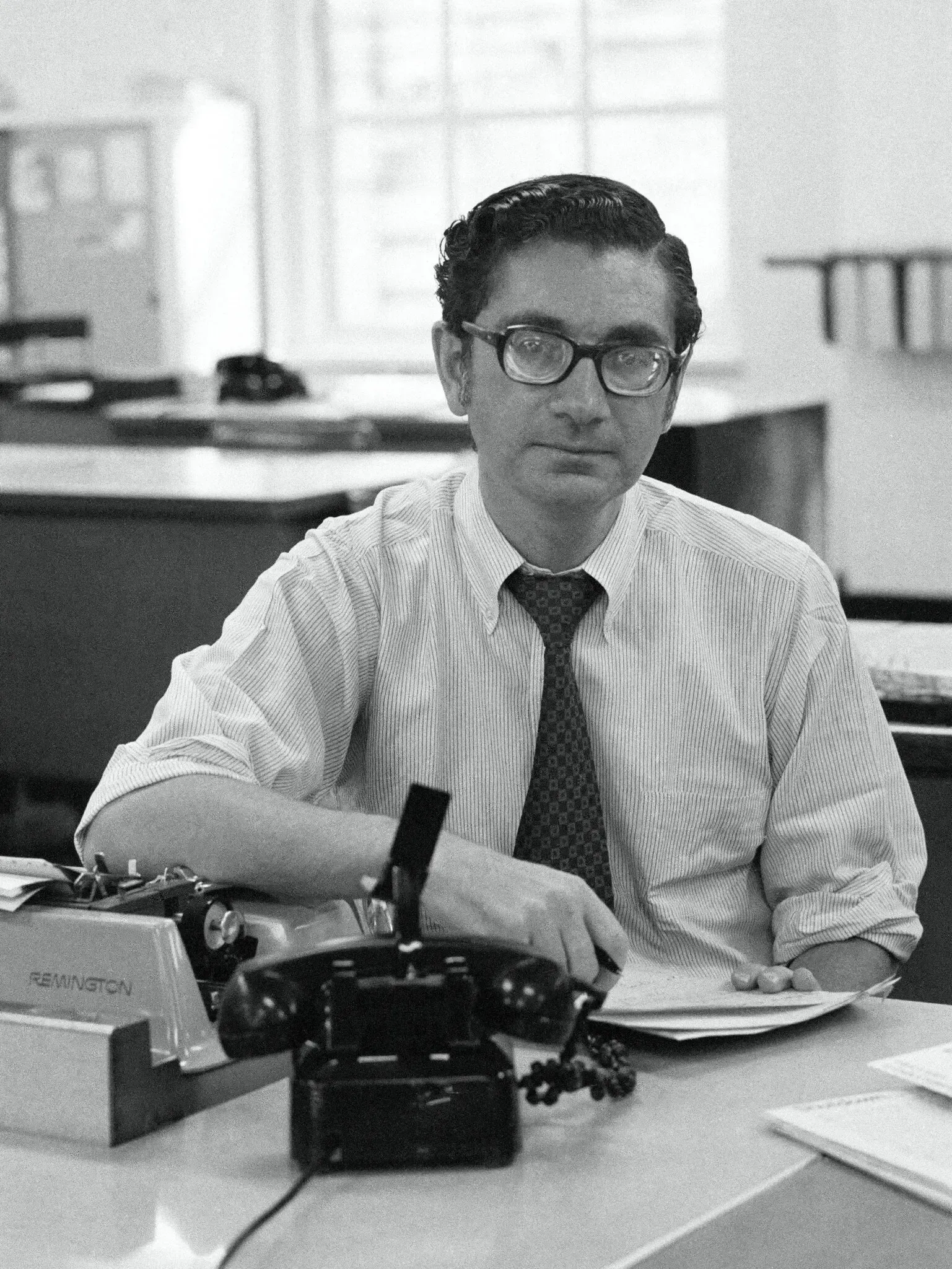

Jim Lynn

A swell fellow, a proud Silurian, that all-round nice guy, Jim Lynn, left us on Aug. 10 due to complications from Covid. He was 88 and a retired editorial page writer at Newsday, where he had worked for 30 years.

Jim, a Princeton University graduate, went to Newsday in 1972 after stints at The Long Island Star-Journal, Newsweek, New York Herald Tribune, WABC-TV and WMCA radio. He was the Trib’s Albany bureau chief in 1966, on vacation in Europe when he got word that the paper had shut down.

His former colleagues at Newsday had nothing but awed references to Jim’s intelligence and wit. James Klurfeld, editorial page editor for Newsday from 1987 to 2007, remembered his friend and colleague as someone who represented old-fashioned virtues. “He was a terrific editor, a very careful fine, fine editor who always improved your writing,” Klurfeld said. “He improved my writing. I won an award for best editorials one year and I owe it all to Jim who I often showed my material to before I published it.”

Carol Richards, editorial page deputy editor from 1987 to 2006, said that during those years the editorial board was strong with smart, passionate people whose political leanings covered a wide range of beliefs. Lynn was the person to count on to be informed on liberal politics. “When we were having a debate about some issue, almost always political or governmental, Jim had opinions that people would listen to,” she said. “He wasn’t a knee jerk liberal; he was a well-informed liberal.”

“He always said he felt so lucky to have had the opportunities that he had,” his daughter, Nina Lynn said. “He also felt a great responsibility to use what he had been given, well and honorably.”

James Dougal Lynn was born in Houlton, Maine, and graduated from high school in Mount Lebanon, Pa., where a teacher recommended that he apply to Princeton. His experience there set him on a life-changing course, his daughter Nora Curry said, which included his first introduction to bagels. “His world opened up in so many ways. He made lifelong friends, he got to be with other people who loved reading and writing and thinking the way that he did, he’d not had that before.”

Dora Potter, Newsday alum, fellow Silurian and his devoted partner of 30 years, said Jim was “thoughtful of everyone.” Besides obvious acts of community service such as after he retired volunteering as a dispatcher for the local fire department, he would do unexpected, ordinary things that would never occur to others. He packed up his extensive collection of Playbills and took the train in from Long Island to give them to an Aids center for actors. He lugged interesting beer cans he’d picked up all over Europe to the delight of a friend back home who had a collection. “He never stopped thinking of others,” Potter said. “He was a steward for us all, he took care of us.”

His daughters agreed, saying their father gave them a set of values to live a life with empathy and public service.

He made one final act of public service: he donated his body to science. “To my dad it was sensible,” Nora Curry said. “It’s like ‘someone can use this and learn from it.’”

A memorial was scheduled for Nov. 6 at the Nassau County Museum of Arts in Roslyn, where Jim was a docent. Potter said it would be both in person and on Zoom. She said she particularly wanted that option so people can choose to be safe, since both she and Jim had suffered from Covid.—By Theasa Tuohy