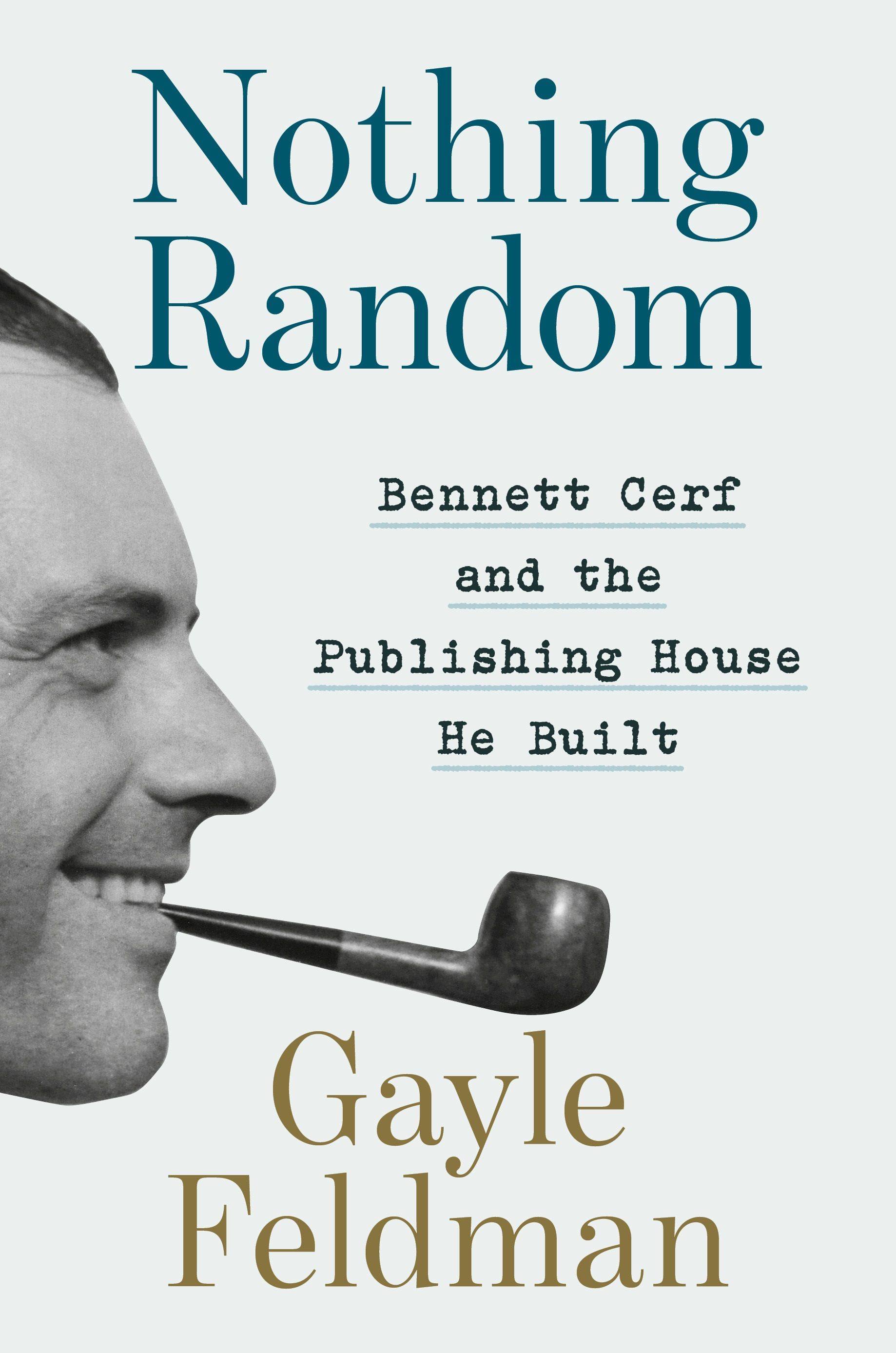

From Dr. Seuss to Truman Capote:

Bennett Cerf, the publisher who changed American literature, forever

Bennett Cerf shaped American literary culture, championing writers from Dr. Seuss to Truman Capote. William Faulkner to Ayn Rand, turning a scrappy upstart into one of the world’s most storied publishing houses.

Author

Gayle Feldman has brought his remarkable life and legacy to the page in

Nothing Random,

Bennett Cerf and the Publishing House He Built,

a biography as compelling Cerf himself.

Join us on March 18, for a fascinating luncheon with Feldman in conversation with Kai Bird, the Pulitzer Prize-winning biographer of American Prometheus, a biography of J. Robert Oppenheimer. Two master storytellers, one unforgettable afternoon. Reserve your seat today.

Public Media Is Staggering, But Not Down for the Count

Like the Boxer in the song, Neal Shapiro says public media suffered staggering punches at the hands of the Trump administration— but is still standing.

The recently retired chairman of the WNET group delivered his candid assessment of public media’s future in a conversation with former Silurians president Betsy Ashton at Silurians Press Club’s Feb. 18 luncheon.

“We are like a boxer, I’d say,” Shapiro told the crowd, who sat in rapt attention as he pulled back the curtain on a looming $500 million federal funding crisis. “We’re staggering. We’ve been hit hard. We’re not down for the count, but there has been damage.”

Shapiro warned of program cuts and shrinking coverage, especially in rural areas, while arguing the real battleground is younger audiences who expect to choose when, where, and how they watch. Platforms like YouTube, he said, are now essential to reaching the next generation, even as public media struggles to monetize and build relationships there.

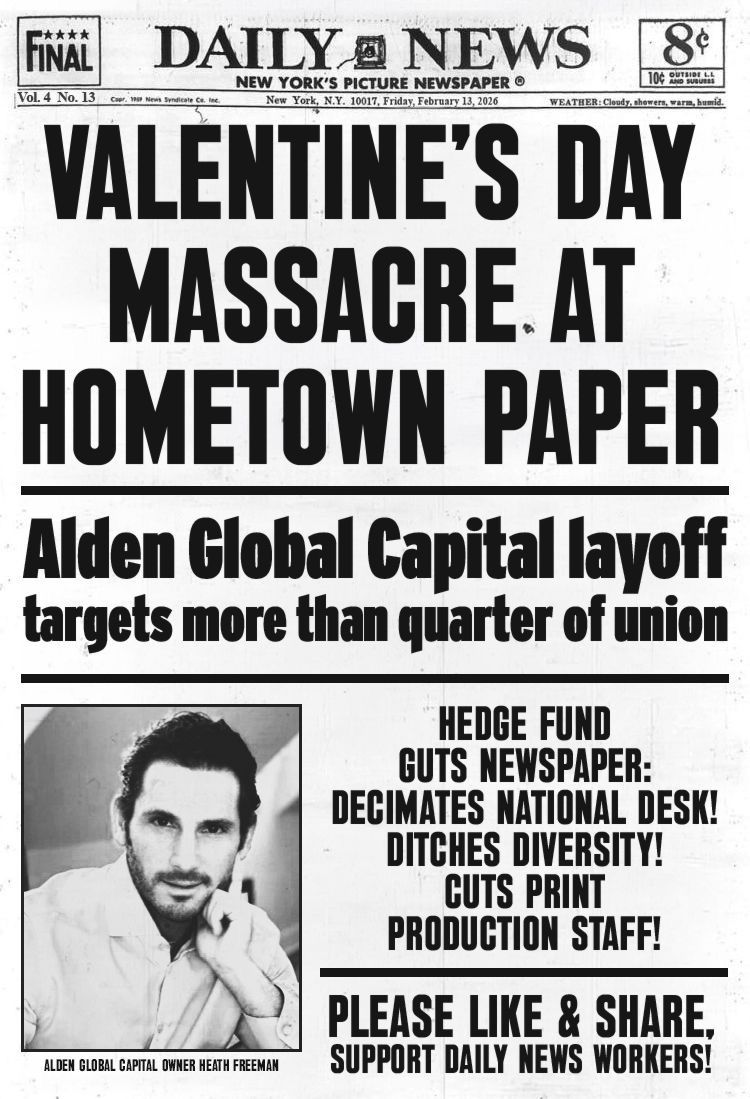

News Media News

About Silurians, by Silurians

The Irrefutable power of Community Reporting

By Adam Stone

On July 12, 2025, The New York Times published a front-page story “UnitedHealth’s Campaign to Quiet Critics,” which included an account of the insurer’s apparent attempt to chill my Westchester County-based investigative reporting....This mega-corporation wanted to silence my local watchdog news outlet—emphasis on local.

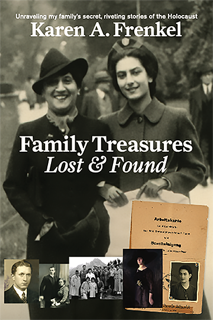

Reporter’s Tenacity Unravels – and Helps Chronicle – Her Family’s Wartime Secrets

By Karen A. Frenkel

My training is as a science writer and technology journalist and producer.... I transitioned to narrative nonfiction with the Family Treasures Lost and Found project, which includes my recently published memoir and tie-in documentary. .Both chronicle my investigative quest to fill gaps in the survival stories of my Polish Jewish parents and sole surviving grandfather.

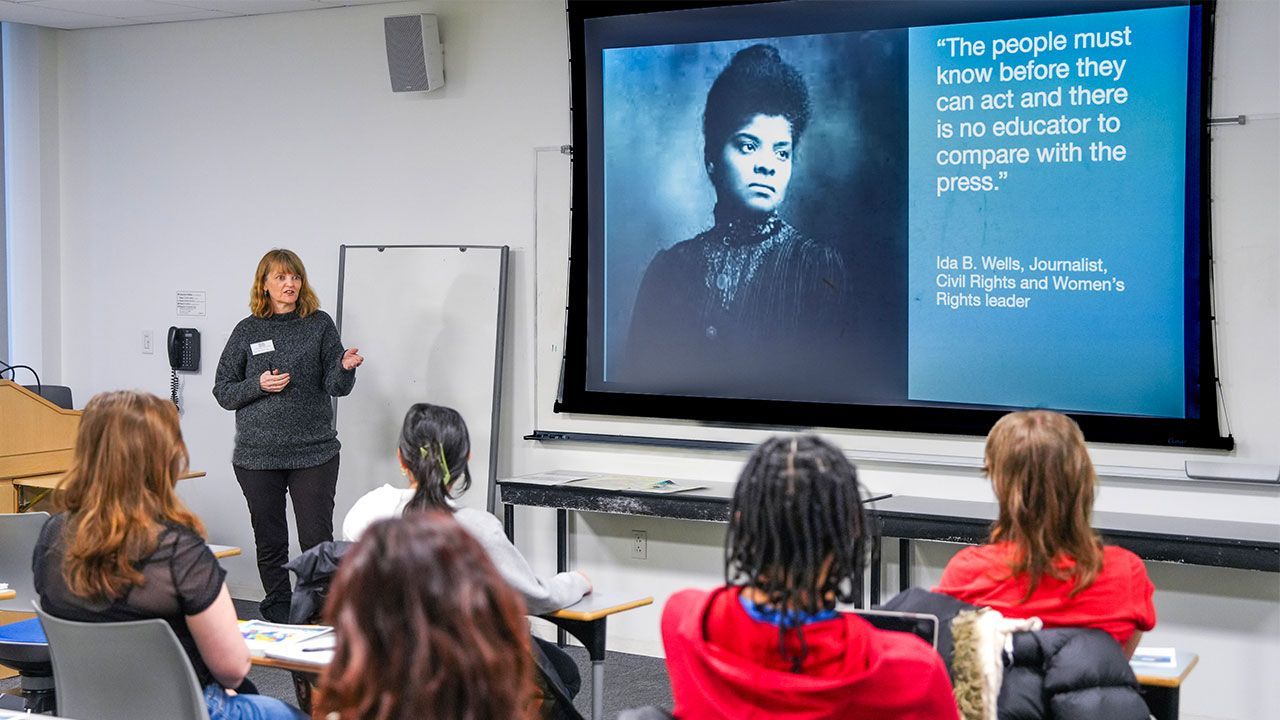

This Optimistic ʻSilurian Newbieʼ Is Grooming The Next Generation of Journalists

By Cathi Steele

I’m a Silurian newcomer, relatively speaking, as I was accepted into this esteemed press club in July 2025. Like you, I’m concerned about—and sometimes downright distraught over—the perilous climate in which journalists and media find themselves.

And yet, I see a future of possibilities.